Work shouldn’t hurt – and this also applies to workers’ mental health.

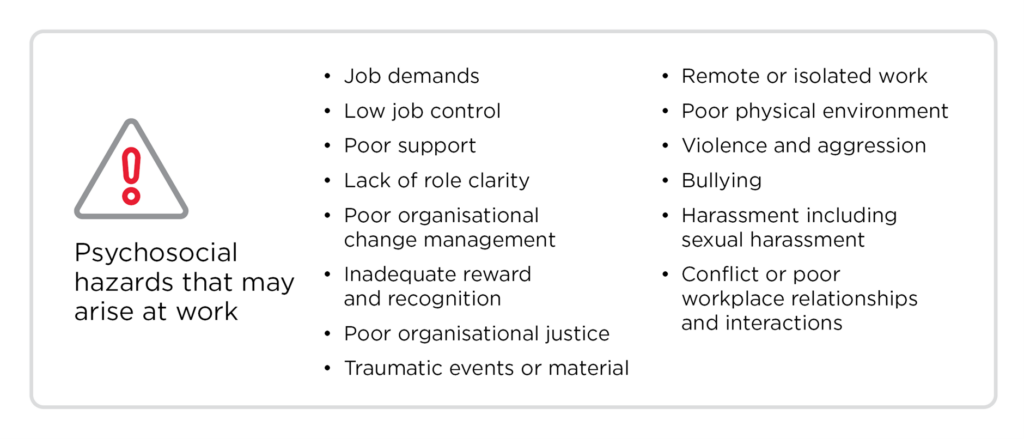

According to SafeWork Australia’s Managing Psychosocial Hazards at Work Code of Practice these can include:

It’s WorkSafe Month and Mental Health Week, so we caught up with the Department of Justice Wellbeing Support Case Manager Liz Moore about mental health in the workplace.

Psychosocial hazards are at the forefront – as these are issues impacting across workplaces – and from January this year, there is a legal obligation for employers to manage these risks. Echoing this, this year’s WorkSafe month theme is Safe Bodies, Safe Minds.

What are psychosocial hazards?

CPSU: Tell us about your role

Liz Moore: After 30 years in Corrections, I’m now working as a Case Manager in the Justice Department’s Wellbeing Support team. We provide support to all staff of the DoJ statewide, including individual case management and psychology consultations, health screenings and mental health check-ins, general wellbeing promotion and workplace training in areas such as Mental Health First Aid, Cultivating Resilience and Vicarious Trauma. The unit has been operating for about two years now and we’ve dealt with over 350 individual staff of the Department in that time, in addition to providing training to many more.

We’re getting really good support from our client base, and I think we’re providing a really useful service to staff. It is much needed, across all areas of the Department.

This is the second Wellbeing Support Unit in the state government, after DPFEM established the first. Other agencies including Health and DECYP are also making inroads into this area, and I think they’ll soon be seen as an essential service for all staff.

Our unit includes some in-house psychologists, which means that DoJ staff can get quick access to a psychologist without a GP referral, at no cost and without waiting times or limited session numbers.

We work with staff who choose to come to us, so for me it’s been quite a change from Corrections – I no longer worry that my clients might be out committing crimes or using illegal drugs to excess, and I no longer contemplate prosecuting people who don’t turn up to appointments! It’s wonderful to deal with clients who are highly motivated to address the issues that bring them here, and it’s also positive that the workplace supports people to attend in work time. This is a different cohort for me – the clients all want to be here and by the time they’re in the room, they’re ready to do the work, so it’s really rewarding work for me too – I love it.

I’m in a Case Management role – we’re the initial point of contact, so we assess people and find out the issues that need to be addressed and together with them we work out a plan for addressing those issues – it’s a collaborative problem-solving approach. We work across the Department of Justice and around the state as much as we can.

People can self-refer or the service can be suggested to them by a manager, supervisor or colleague. We’re finding that we’re getting a lot of referrals from people who attend and then suggest to their colleagues that they could also get value from attending. That’s a real positive for us. Particularly in the Prison we’re noticing that cultural shift, which is really encouraging in an environment where once help-seeking was not really the done thing.

We’re located separately from any other Department of Justice services, so it’s discreet for workers to visit, and we have really strict protocols around client confidentiality.

What impacts can a workplace have on an employee’s mental health?

The workplace has a huge impact on the mental health of staff, and that’s why it’s so important that the issues that are causing stress to staff are properly addressed. In dealing with workers in this role, I’ve been surprised by how many of them identify factors such as not feeling valued, supported, and respected as part of their overall concern. These are things that to me seem to be relatively easy to change.

Workplace stress can contribute to changes in mood including anxiety and depression, irritability with colleagues and conflict within teams, and this can have impacts beyond the workplace including poor sleep and negative impacts on families. If you notice that you’re feeling excessively frustrated, crying more than usual, crying at work, or taking your frustrations out on those around you at home, recognise that this isn’t okay and check it out with someone who can help, whether that be a GP, other professional, Mental Health First Aider, good friend or colleague, union Delegate, your manager, or your Wellbeing Support team.

Noticing that those things are not normal for you, and knowing that’s not okay and that the workplace has an obligation to help take care of people’s psychological health and then taking some sort of steps to address that is important and should be encouraged by all workplaces.

Psychosocial hazards – we’re hearing about these more and more – how critical are they to wellbeing?

There was new legislation [Link] passed recently that now requires the workplace to take care of workers psychosocial safety and to ensure their mental health in the same way as their physical health. [link: https://www.worksafe.tas.gov.au/topics/laws-and-compliance/codes-of-practice/cop-folder/managing-psychosocial-hazards-at-work]

It’s just as important to recognise the workplace impact of psychosocial hazards as physical hazards that have traditionally been identified as risks, such as a slippery floor or dangerous wiring.

The Justice Department’s Work Health & Safety training tells staff that ‘the Department is committed to ensuring that no person will suffer a preventable injury and/or illness, and that the protection of our people is paramount and we will support our staff not only with effective systems but also with leadership and individual commitment’.

We are trained to put peoples’ health, safety, and wellbeing first and to identify hazards and remove them if possible, and this needs to apply equally to psychosocial risk factors.

These risk factors can include poor supervision or lack of support, high job demand, lack of role clarity, lack of job control, frequent organisational change, remote or isolated work, unreasonable work demands, unreasonable working hours / schedule, inadequate reward and recognition, bullying and lack of job security.

These factors are absolutely critical to the wellbeing of staff in the workplace. We’re often hearing from clients who don’t feel that their workplaces are sufficiently resourced to undertake the work they’re expected to do, putting pressure on everyone in the team. A seemingly simple measure that I have observed that could improve workplace morale significantly is filling vacancies quickly, to reduce the additional burden on the staff who remain when others resign, move workplaces, or go on long term leave.

I’m thinking that all of these issues are ones that feature across the public sector – and now it’s legally required that they are identified and removed from the workplace. So, people can feel confident that there is more support available to them, and that it’s reasonable to raise these issues. A Productivity Commission report showed that psychological injury in the workplace cost $40 billion dollars in Australia in 2020 – it’s a significant issue. We’re also hoping that earlier identification of problems and appropriate intervention will help to reduce the number of staff ending up on Workers Compensation, which has a high personal and financial cost to both the agency and the individual.

Now there’s an obligation on the workplace to take care of mental health, it’s helping to de-stigmatise the issues and making it okay for people to seek help and to expect that the workplace will support you to do that.

We see a lot of people who feel buried by the workload and the impossibility of getting on top of it all. That’s a terrible feeling for people to have if there’s an expectation that they should be able to do that. But if the expectation is reasonable, and there is a shared understanding that everyone can go home on time and that you’re not going to get to the bottom of your work pile today, that’s a different story. But if the expectation is that you will stay until it’s done or there are critical deadlines like court sessions that have to be met, people end up working through breaks, working late and not taking leave. That’s a really bad message for workers and it’s clearly inconsistent with the new psychosocial hazards legislation.

What is your advice you have for workers, when it comes to mental health and wellbeing?

There can be a danger of problems being individualised, and the worker being made to feel responsible when the issues are organisational, structural or systemic.

Yes, self-care is really important to ensure that employees are in a good state to tackle the pressures of challenging and demanding roles. This includes all the obvious measures like ensuring good sleep, good nutrition, exercise, getting outdoors, staying connected with others, talking about issues that are causing concern and limiting screen time and excessive use of alcohol and drugs. Sometimes it can be useful to check in with yourself by imagining that your energy and resources are a battery, and thinking about what percentage your battery is charged to – 80%, 40%, less than 20%? Being aware of how you’re feeling is the first step towards being able to get on top of difficulties.

However, in cases where the issues are systemic and organisational, rather than individual, such as workload that simply can’t be achieved within the allocated timeframe and with existing resources, I would encourage staff to get informed about your options, name up your concerns using the appropriate channels within the organisation and keep pushing to have these factors recognised and addressed. The workplace has a legal responsibility to take care of the health and wellbeing of staff, and it’s just not appropriate any more for these matters to be ignored or for the onus to be put back onto the individual to manage them.

Use your Department’s Wellbeing Support service or Employee Assistance Program if you have one, and advocate for one if you don’t – I have no doubt that it has been found to be of significant value to many of the DoJ staff members we’ve seen over the past couple of years. Your union is also a good source of information and support for staff who are struggling and want information about the options available to them.

For managers and supervisors, I’ve been surprised by how many people I’ve seen in this role who just want to feel valued, respected and supported in the workplace, and what a difference those things make to workers’ quality of life. These seem to be relatively simple matters to address, without major impacts on the budget!

My view is that if we all strive to behave as decent human beings in the workplace and approach issues as adults with kindness and understanding, a great deal of the angst we are seeing could be reduced.

It’s in everyone’s interest to have sustainable, long-term and happy workforces but it does not always work out that way in practice. So get informed about policies and practices that can support you in your Department. For example, Justice has a really good policy about flexible work options but I’m hearing that some managers don’t allow workers to use it, and this needs to be handled higher up – because that’s not a reasonable response and I don’t believe it would be supported by the Department’s senior management. The union is a great point of contact for raising these issues too.“

Work in the Department of Justice? You can contact Wellbeing Support on 6165 6718 or at wellbeingsupport@justice.tas.gov.au. This is a service DoJ workers can access during worktime.

Workers in Police, Fire, Emergency Management and Ambulance Tasmania also have a similar service set up – find out more at https://www.mypulse.com.au/, on 6173 2080 or at wellbeing@dpfem.tas.gov.au

CPSU Members: our CPSUDirect Team are here if you are wanting to know your rights on psychosocial hazards or if you are receiving pushback to having these rights. Contact CPSUDirect at CPSUDirect@tas.cpsu.com.au or on 6234 1708.